Back Up The Mountain:

Jane’s addiction wen out on top back in 1991 after jumpstarting a cultural revolution. Steven Chean meets the “relapsed” band in their L.A. studio as they prepare for the expedition back up the peak, and details the band’s past triumphs of art and attitude over commerce and compromise.

“Oh m’god, you are the best-looking guy in women’s clothing!” exclaims a bottle-blonde wisp

of a young woman, her friends giggling in agreement. The object of their admiration saunters by as if on a catwalk, making his way to the nearest mirror, where he gazes approvingly at his white leather hiphuggers with the moccasin-laced fly, and the black, ankle-length overcoat with the faux poodlehide lapel that drapes his bare torso. With one last glance, he shoots a thumbs-up to a woman who stands anxiously at a wardrobe rack.

The final piece of the puzzle, Dave Navarro has officially entered the building, and with the unselfconscious flamboyance of a born rock star, he nonchalantly blows past a hallway full of admirers. Ducking beneath a sign reading: “Welcome back stage! Where high-tech and lowlife collide,” he joins his fellow “lowlife” for the photo shoot already in progress.

“Whooo-ooo- foxy!” hollers the everimpish Flea, adorned in porkpie hat and a whole lotta fishnet.

From a nearby sofa, a grinning Stephen Perkins and Perry Farrell join in, appraising the fashion plate. “So fine. So fine,” Perkins says, laughing.

“Uh-huh. Hope you brought a lot of film,” Farrell says wryly, glancing at the photographer. “He’s gonna need a couple dozen rolls all to himself.”

Beneath his red-devil goatee, Navarro offers a rare smile. He accepts the ribbing as it is intended-good-naturedly, from old

friends who, over the course of the past 10 years, have evolved into something of a family. “Well, I guess if we’re gonna do this, we may as well do it right. Right?”

Welcome to homecoming week, Jane’s Addiction style.

During the past few months, Farrell, Navarro and Perkins-three of the band’s four original members have fallen back on their old musical habits. With the addition of the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ bassist, Flea, they’ve taken to calling themselves a “relapsed” version of their former incarnation. Rehearsing their new album, Kettle Whistle, amid the tikidecor-studded space that serves both as an artists’ collective and as Farrell and his manager’s office, the group have been literally dusting off their history. And while rummaging through crates of demos, studio tracks and taped live performances playing most of them for the first time in half a dozen years-Jane’s Addiction have had the opportunity to rediscover the magic that drew them together in the first place.

“There was definitely a power that made four music] really special,” Perkins says. “It was real; it reflected what was happening on the streets at the time, which is why it made such a deep connection with our fans.”

‘Yeah, being in a room with these guys again and playing the old stuff, it’s like this beautiful energy’s there again, blossoming like a flower,” Farrell emotes. His voice trails off as he considers the nasty accusation that inevitably accompanies “getting back together” – that it’s nothing more than an attempt to line the pockets. It’s a concern he’s lived with since the band’s final days, when he remarked that another Jane’s Addiction album would be “gluttonous one big corporate buy out.”

“To be honest, there was a moment when I was worried if this was the right thing to do,” Farrell says. “I didn’t want it to be-or seem-like an exercise in self-indulgence, but I know better. I mean, we already got the car and the house, man. This is about art; it’s about passion.”

In an era when bands are reuniting by the droves to cash in on their names, Farrell’s concern is warranted. But indulging in what has become the Great Rock ‘N’ Roll Cliche Of The ’90s doesn’t quite jibe with his, or Jane’s Addiction’s, m.o. After all, this was the band that, during their tumultuous five year career, acted as a virtual battering ram against the forces of convention. From inception to demise, Jane’s made a name for themselves by pushing the envelope, challenging the limits of a recording industry that was languishing in grotesque self parody. And, no, it’s not a coincidence that they were “bred and spread,” according to their debut’s liner notes, in Los Angeles, the epicenter of grotesque self-parody.

“I think there’s a reason that we all met up here in LA.,” says Farrell. “We were four souls looking for the other side. We all wanted to break away from the sameness of all the shit around us. We wanted to make music that nobody had heard before and bring it to the kids on the street in a way that hadn’t been done. And the beauty of LA. is there’s always plenty of shit around, and even more ways to break away from it.”

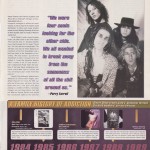

The shit to which Farrell refers is mid ’80s MTV and mainstream radio, whose progeny, a tangle of homogeneous big-hair bands, worked their glam-rock shtick in the multitude of clubs dotting the Sunset Strip. Ratt, Poison, Warrant… it was 1986, and these names were unfortunately only too familiar to Perkins and Navarro, a couple of 18-year-old speed-metaI heads who had a yen for something harder, deeper, different. What they found were Farrell and bassist Eric Avery, veterans of the goth-like outfit Psi Corn and collectively a one-way ticket to the heart of darkness.

“I’d always considered myself a day person,” Perkins recalls. “Basically a nice Jewish kid from the Valley. Suddenly, I’m playing my first Jane’s show to the accompaniment of a full-on motorcycle revue with transsexual strippers fooling around with fire

and snakes, and porn movies playing behind a guy selling corn dogs. I mean, this was a whole new world to me.”

A Jane’s Addiction show was a guaranteed excursion to the extreme. By turning their backs on pay-to play, high-profile venues in favor of basement and warehouse gigs, the group were liberated in ways they initially couldn’t have imagined. By resigning themselves to the fact that the obvious channels of exposure were out of the question, they held the key to catharsis. “Every urge and emotion was there for the taking onstage once we knew that we weren’t going to play ball with the major labels and doll ourselves up like everyone else and line up to kiss their asses,” says Farrell. “I mean, we were home free, We could do whatever we dreamed of-and we did.”

Not so much a gig as a primitive rite of passage, a night with Jane’s Addiction was a trance-inducing experience, one that provided release through ritual. Alternately adorned in Day-Glow girdles, black vinyl body suits and neon dreadlocks, Farrell went off like a shaman at the mic, leading his cohorts through sets that were as spacey and narcotic as they were skull-rattling and frightening. His hard lived autobiographical lyrics were animated by a seamless blend of art rock, psychedelia, funk and metal that offered up moments of apocalyptic rage, weaving them into flourishes of sublime beauty.

After commiting their combustible set to a self-titled album on the LA.-based indie Triple X, the band watched their reputation grow. Crowds swelled from a few hundred to a few thousand, and the quartet found themselves in the midst of an intense major-label bidding war.

So much for staying underground. “It was a weird time,” Navarro recalls. “We’d been around a little over a year, to the best of our knowledge doing everything our way-which most bands would have considered the wrong way. And here we were with all these labels after us. At first we were distrustful of a big corporation, thinking they would fuck us over. But we covered our asses and went into it thinking, ‘Who’s gonna have our backs when things get nasty?”‘

Farrell’s colorful antics made for an eventful journey through stardom. While the band edged closer to the ranks of mainstream success, they distanced themselves from the maw of crass commercialism by retaining-no, boasting-their artistic freedom. Farrell employed the covers of Jane’s two Warner Bros. albums as canvases for his unique aesthetic predilections. Nothing’s Shocking’s naked-Siamese-twin-inferno sculpture and Ritual De Lo Habitual’s menage-a-trois-Santeria(ish)folk-art composite managed to offend the moral majority, as well as many of the nation’s record distributors. In total, seven major retailers refused to carry Nothing’s Shocking, aII but two of which buckled under the weight of Warners’ capital clout.

As for Ritual, in order to quell another ruckus, the label struck a deal with Farrell. “They told me that if I designed another cover, they’d release the first cover,” Farrell says. “So I did, and they released both.” The alternate cover was all-white, featuring an inscription of the First Amendment and a brief love letter to the champions of censorship. “The only reason I put the First Amendment on there is because I’d be lost without it. I need that protection because when it comes to art, I’ll only extend. I won’t compromise. Period. That’s the backbone of the band: Never compromise; otherwise you’re dead. You’re a victim, and they will dictate your career from that point on.”

Farrell’s life philosophy guided Jane’s Addiction to unforeseeable heights, their defiant character ever intact. By 1991, not only had Ritual gone platinum, but the band, who only a few years prior were playing to a handful of bikers, transsexual strippers and corn-dog vendors, had sold out Madison Square Garden and played four consecutive nights at the Universal Amphitheater. They headlined promoter Farrell’s first Lollapalooza tour and enjoyed mass radio exposure. Even MTV, which had once refused to air the video for “Mountain Song” due to its depiction of nudity (only later to give in when Farrell prohibited any editing), acknowledged the group with constant rotation and the Best Alternative Music Video award for “Been Caught Stealing.” The quartet that had purposefully bypassed the obvious route to fame had stumbled upon it anyway-and they’d done it on their own terms.

Jane’s Addiction’s sheer gale-force wind as a musical entity might help to explain their present “relapsed” condition. If the band’s past glories were powerful enough to draw three quarters of the original line-up back into the fold, then their former excesses were enough to keep out the remaining one-quarter. “And you can’t call it a ‘reunion’ without all original members,” Farrell states matter-of factly. “All I’m going to say is we asked Eric [Avery] to join us, and I’m sad he didn’t want to work with us… although I will say that I think it’s very selfish of him which is so typical of him.”

For Avery’s part, his refusal to enlist underscores the interpersonal tensions that tore Jane’s Addiction apart during their final months. At the time, the bassist was two years sober and fighting to stay that way. Farrell, on the other hand, was speaking openly about his use of drugs and proclaiming their benefits. But that was merely a superficial indication of a deep rift. According to Avery, who spoke about the . relapse” during a break from rehearsing with his new band, Polar Bear, there were larger issues involved.

“Some people think I hate Perry. I don’t. Not really. I resent certain things about him,” Avery admits. “When the two of us co-founded the band, it was a creative democracy. We were just a bunch of kids having fun. But Perry’s sort of a one man three-ring circus. He has to be the center of attention, and it’s hard for him to deal with other people in true partnership. Toward the end, the band sort of became a cult of personality around him, and I wasn’t in the picture anymore. I wasn’t getting credit for the music. But that was livable. What wasn’t livable was that I didn’t have as much input anymore.”

This past May, nearly six years since he and Avery last spoke, Farrell dropped in on a Polar bear show in Los Angeles. He and Avery talked about old times and agreed to meet again over lunch. For all intents and purposes, the meeting ended before it began. “I had a totally personal agenda,” Avery insists. “I figured I’d put the past behind me, so why not hang out and shoot the shit like old friends? But before we met, I heard through Perry’s manager that the only reason he wanted to meet with me was to get me into the reunion. As usual, it’s always him and his thing. It was selfish, and I just don’t want to be around that kind of person or atmosphere anymore.”

Gazing out at the emptiness of the dirt lot behind the studio, Jane’s Addiction uniformly grow silent at the mention of Avery. That is until Navarro who stayed close with the bassist after the band’s break-up. working with him in the one-off studio project Deconstruction takes it upon himself to bring the subject to a swift conclusion. “All I can say, and I think I speak for all of us, is we look at this as an opportunity to correct the mistakes that were made in the past-for all of us to play and interact as adults,” he says. “But that’s obviously not going to happen, at least not with him, and we can’t-and won’t-beat ourselves up about it.”

It’s understandable that the Farrell-Navarro-Perkins troika would care not to dwell on the Avery issue, what with a juggernaut of a bassist like Flea now in their camp. Five feet seven inches, 140 pounds of human spark plug, Flea may be just the boost Jane’s need to recapture their old energy.

“We love Flea,” Perkins says, beaming. “He’s a B-12 shot for the band; he’s taking us in directions we never thought possible.”

“It’s crucial to play with an enthusiastic person,” Navarro adds, “especially one who’s got the chops to back it up. If there’s any hesitation or fear, especially in the embryonic stages, your end product is going to appear that way. And Flea’s nothing if not fearless.”

Sitting Buddha-like atop a stack of pillows, Flea drinks in the praise, grinning his trademark gap-toothed smile. He’s evidently aware that his presence in the line-up may seem awkward, and that it will inevitably alter the group’s sound, but he doesn’t appear concerned. His confidence may stem from four years of working with Navarro, becoming intimate with the guitarist’s style in the context of the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Or maybe it’s just the fact that he’s followed Jane’s since their inception.

“Man, I remember playing this tribute to Jimi Hendrix at the Roxy back in ’86,” Flea says with a chuckle. “I was so excited. Perry jammed, too. And then, the next day, in the [Los Angeles Times], there’s a big picture of just Perry. I’m, like, ‘Shit! Who the fuck’s that guy?’

“Then I saw Jane’s play, and I realized what an awesome band they were. And even though my band was coming from a totally opposite place, I could relate to their music that intensity. I mean, I knew I was a lucky son of a bitch when they asked me to play trumpet on (Nothing’s Shocking’s] ‘Idiots Rule.’ No question about it. But then I got luckier: I became part of their family, jamming with these guys all the time. Even recently in Porno [For Pyros].”

In fact, the “relapse” might never have occurred if it weren’t for Flea’s involvement. The project’s impetus was a six-month-long intermingling of Navarro, Flea and Porno For Pyros. It grew from their collaboration in February ’96 on Porno’s “Hard Charger” from the soundtrack to the Howard Stern movie Private Ports, then from their live performance of “Mountain Song” at the film’s premiere. It was followed by renditions of various Jane’s songs at subsequent Porno shows.

“There was never an ‘official’ decision made to get the group back together,” says Farrell. “It was just this totally organic process where we felt this amazing chemistry at work, and if there’s one thing I know, it’s that you don’t deny chemistry.”

The band seemingly fell back together, so they are unsure just when, or if, they will break apart once again. Beyond a five week tour of North America, they’ve imposed no time constraints or expectations of any sort. And this attitude spills over into their many varied endeavors. Broach the subject of the future of the Chili Peppers or Porno For Pyros, and what you’re likely to encounter is a collective whenever, a quartet of shrugs. “There’s still a Chili Peppers,” says Flea. “We’ve just taken time off. All those rumors about a breakup are bullshit, the kind of stuff that’s made up by the press. We’ll start writing again, but in our own time. Probably later this year. Maybe not. We’ll see how things go.”

“Right,” adds Farrell. “Porno’s got something in the works right now. But that’s for next year. What we’re doing what we want to do-is focus on the here and now. This amazing thing. These songs. This new album.”

The new album in question is, more or less, the band’s best-of. Not a greatest-hits package, per se, but a collection of personal favorites-and the best performances of those favorites, at that. “I’ve got 500 tapes in my closet at home, and Warners has 10 shows that they multitracked,” Perkins explains. “We heard maybe 50 versions of each song and narrowed it down to the best two of each. What we looked for most was attitude-something that represents what was going on at the time. If it’s raw, fine, as long as it’s got a vibe.”

Sitting alongside a smorgasbord of live performances, previously unreleased tracks and two new songs (‘Kettle Whistle” and “So What?”), there’s the demo of “Mountain Song” that got the band signed to Triple X in 1986, a laid-back Farrell/Navarro duet of “Been Caught Stealing,” and a rediscovered version of “Ocean Size.”

“We listened to 25 to 50 live versions of ‘Ocean Size’ in the studio,” says Perkins. “Then I found a demo that Warners gave us money to do back in ’88. We did it to prove to the label that we could produce ourselves. I called up the guys and played it over the phone. They were like, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s the shit, dude! That’s the one!’ The rest of [Kettle Whistle] is like that, too: the shit!” With the photo shoot behind them, a reborn Jane’s Addiction head back down the long hallway to their recording area, where they continue to brush up on an impressive catalog.

A collective smile fills the room as someone punches the playback button on the control board and the ethereal Eastern sounds of ‘Kettle Whistle” begin to drift into the air. Farrell, dancing in place, harmonizes over the rough cut of the song. His voice is surreal, almost childlike. Slinging a guitar strap over his shoulder, Flea joins in, laying down a hypnotic bass line while he bobs up and down in a small circle. Glancing over at Perkins, he grins mischievously before leaping up on a bass drum. For the next 20 minutes, the two are the tightest rhythm section in recent memory, turning out a bottom end that is equally menacing and majestic.

Crouching down by the control board, Navarro turns up the volume, one level at a time, until the room practically begins to quiver. He lights a cigarette and shifts his attention from the grid of knobs and flashing lights before him to something far more telling going on in a nearby corner. Farrell sees it, too; he’s been watching it appreciatively since the impromptu jam session began.

“That’s it,” he whispers, pointing to a young woman who sways gently against the wall. Her eyes are closed, her presence taking on the overall effect of a dream. “Anybody asks me-that’s why I say we’re doing this project. Look at her. She’s unnndulating and smiiiling She’s turned on and doesn’t care about anything else right now. Man, I love turning people on like that, and if that’s what we can do, then we’re obligated to make music together.”

– Steven Chean

Alternative Press 12.97 p56-65

- Cover

- TOC

- Page 1

- Page 2

- Page 3

- Page 4

- Page 5

- Page 6

- Page 7

- Page 8

- Page 9

- Page 10

You must be logged in to post a comment.